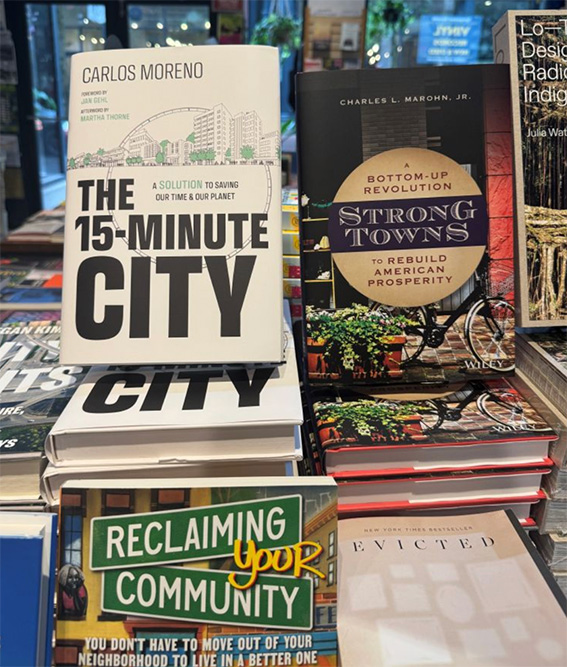

Global research shows that a growing number of people choose to age in the communities they know and love, calling for cities to support active, safe and inclusive urban living for all ages. One promising answer to address this is the 15-minute city—a concept developed by

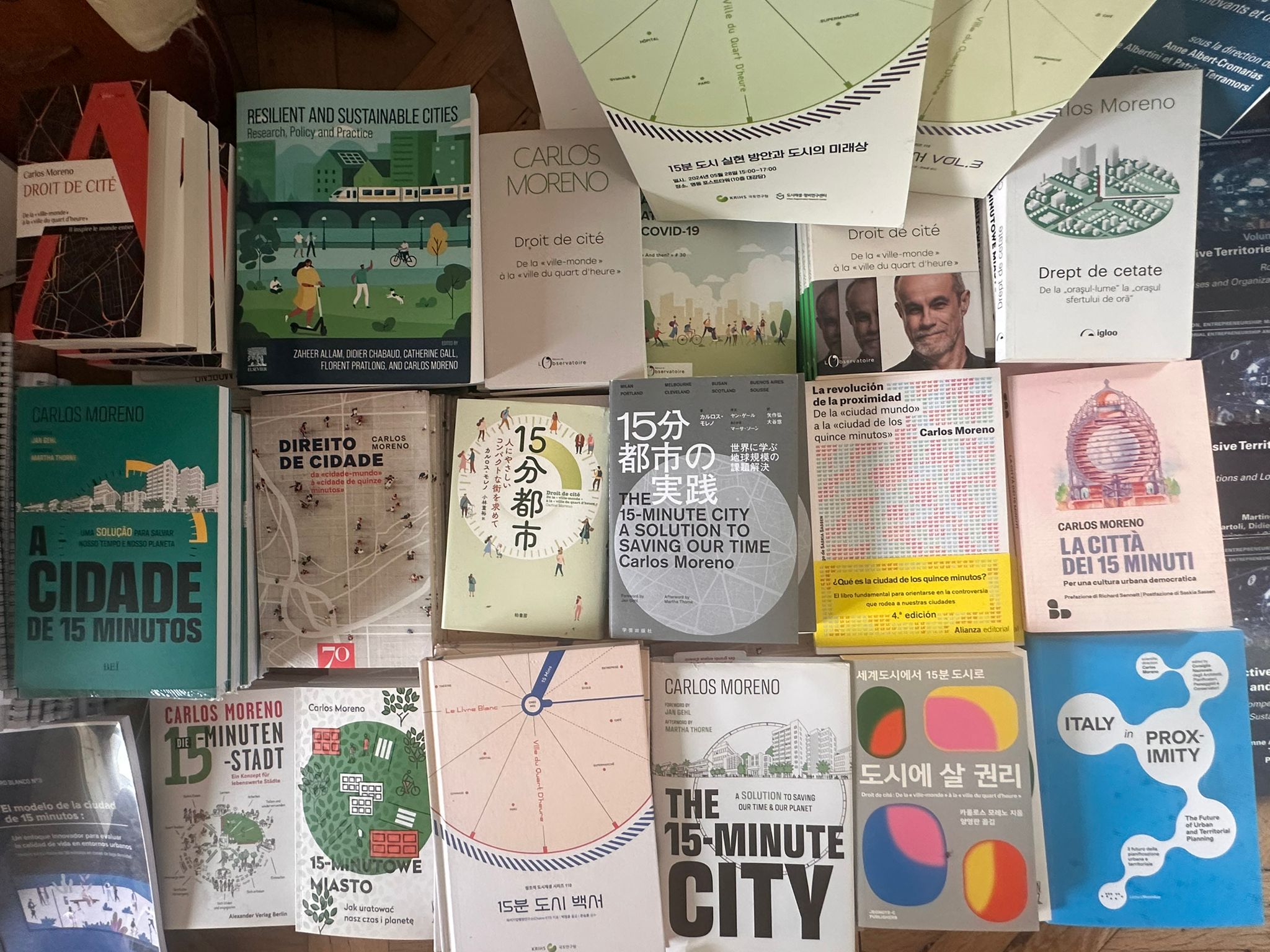

Professor Carlos Moreno that reimagines neighbourhoods where essential services, from healthcare to green spaces, are all within a short walk or bike ride.

First embraced in Paris under Mayor Anne Hidalgo during the pandemic, the idea has since spread to cities like Busan, Melbourne and Utrecht. By prioritising proximity and community over distance and isolation, the 15-minute city addresses urgent urban challenges—from ageing populations and climate resilience to the rise of AI in planning.

In this conversation, Professor Moreno shares how this approach can create inclusive, age-friendly environments. From improving last-mile mobility to designing intergenerational public spaces and tailoring services for older adults, the 15-minute city offers a blueprint for healthier, more connected and future-ready communities.