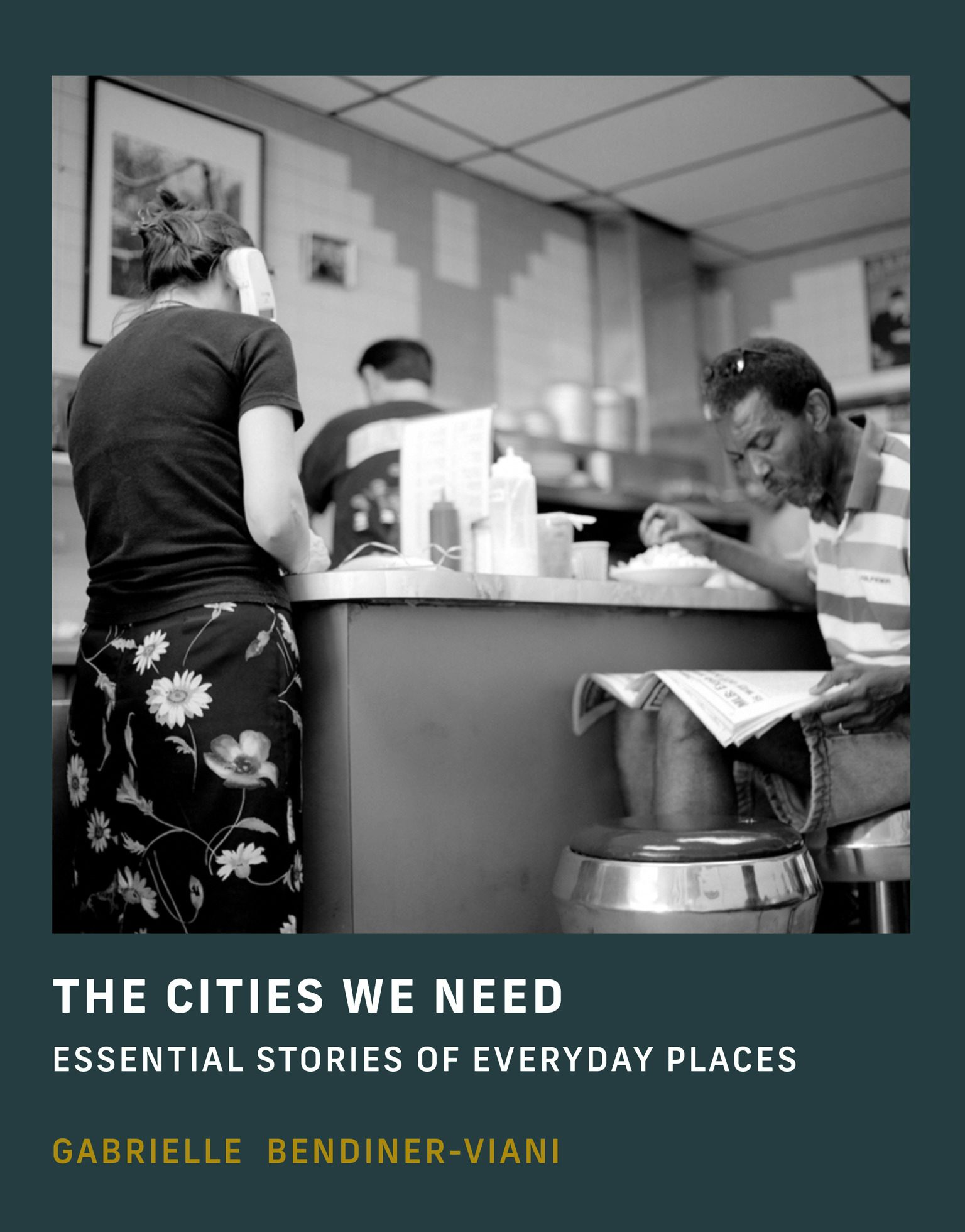

Gabrielle Bendiner-Viani’s work in urban planning and design explores the profound relationship between the places we inhabit and our sense of self and community. In her book "

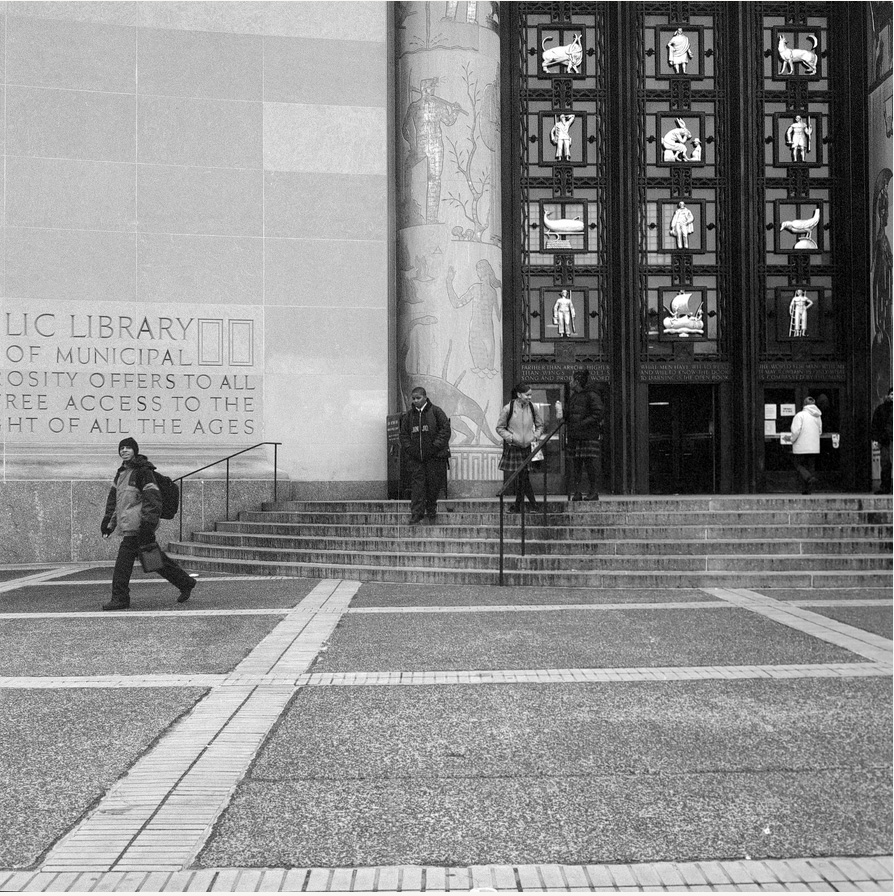

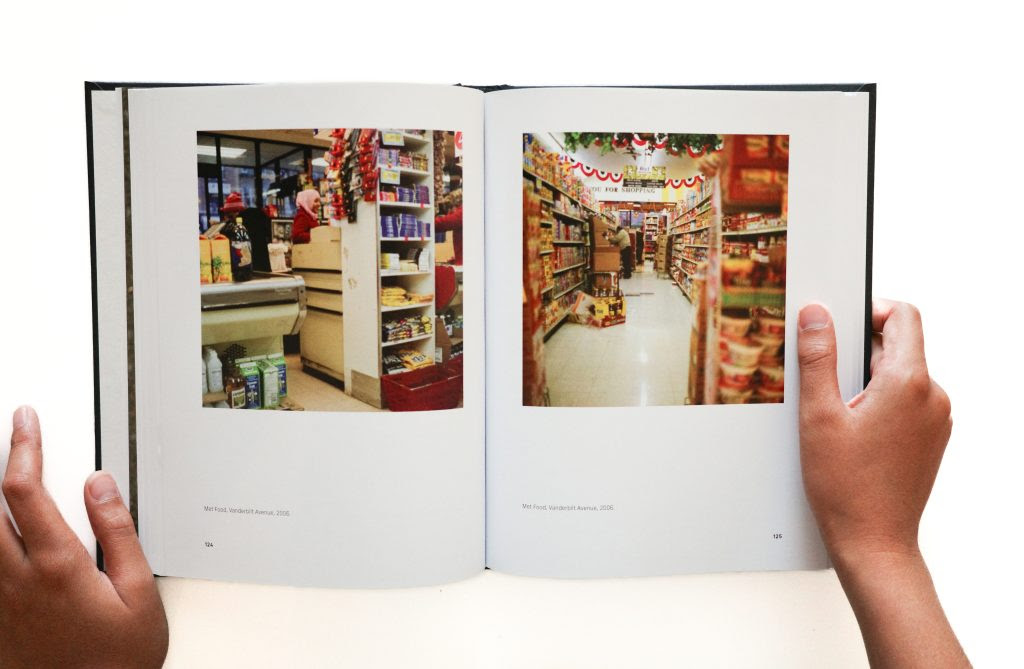

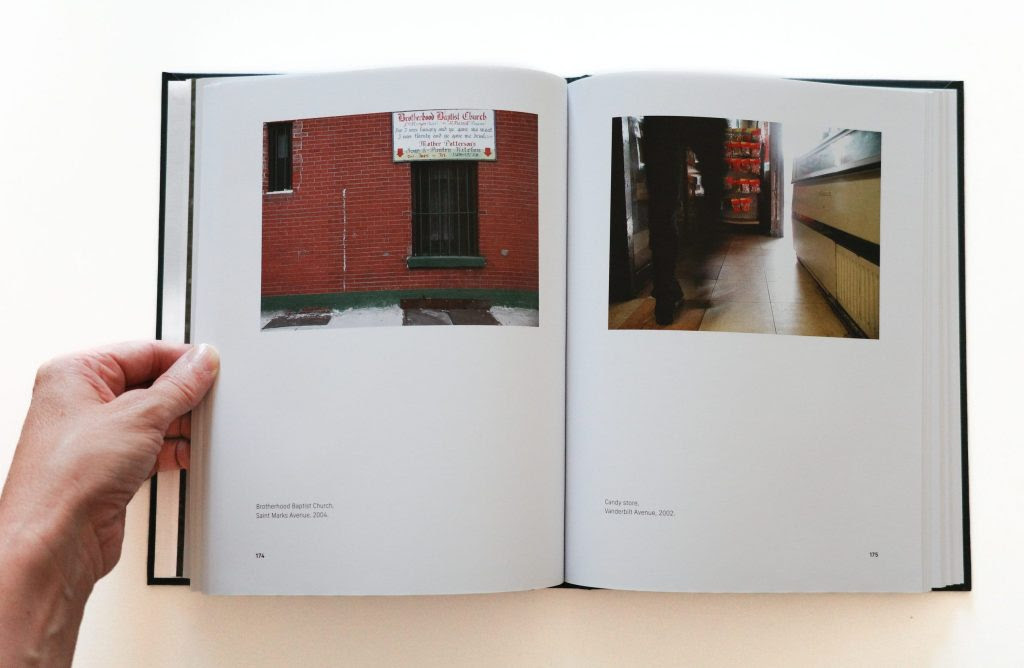

The Cities We Need: Essential Stories of Everyday Places", (MIT Press, 2024) she delves into how everyday spaces—often overlooked—play a critical role in shaping our personal identities and fostering meaningful connections among individuals of all generations. Through her research, interviews and photography in New York and Oakland, California, Gabrielle highlights how public spaces, from diners to libraries, serve as vital hubs for both personal growth and community building. In this interview, we discuss the importance of preserving these spaces amidst urban development, the challenges posed by gentrification, and how cities can be redesigned to combat isolation and promote social cohesion.